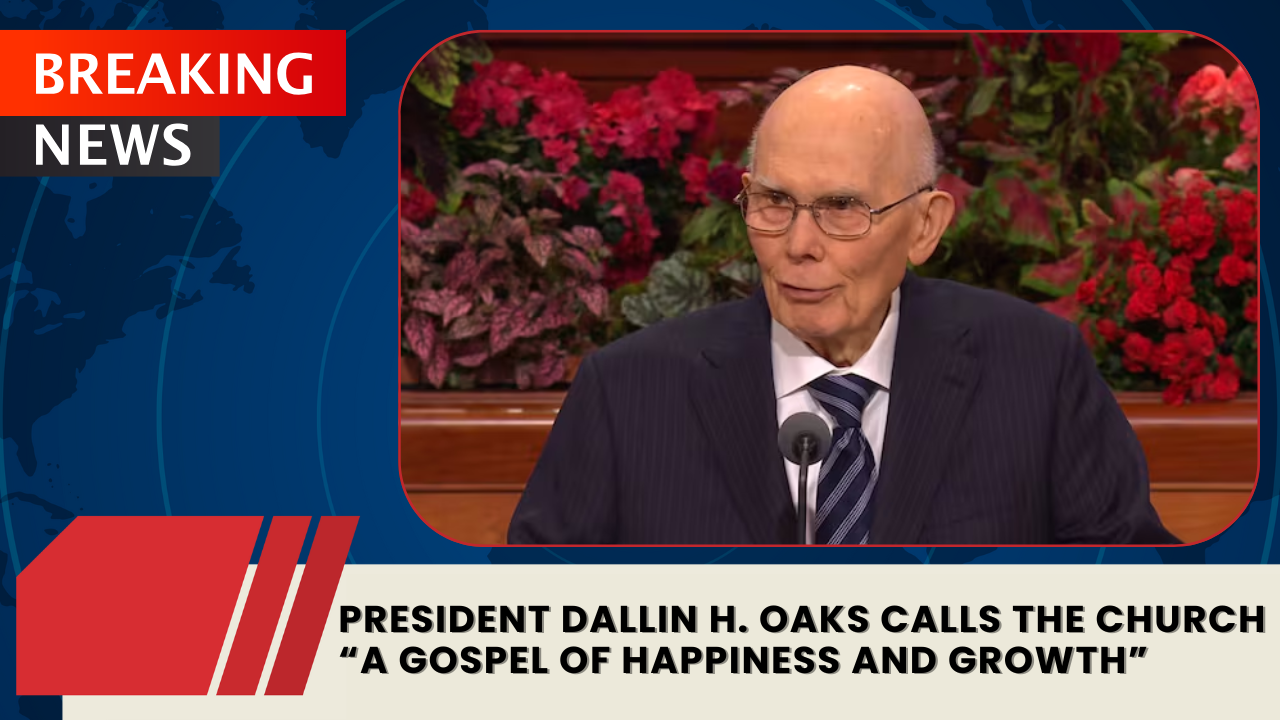

In a major development within the global Christian landscape, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) remains unique among prominent U.S. faith traditions in that its highest leader serves until death. Last week, 93-year-old Dallin H. Oaks was installed as the 18th president and prophet, following the death of Russell M. Nelson at age 101 on September 27.

Oaks’s appointment comes amid a leadership team facing significant age-related questions: his first counselor, Henry B. Eyring, is 92; his second counselor, D. Todd Christofferson, is 80; and four of the twelve apostles are in their 80s.

Why the question of succession matters

The conventional “serve until death” model presents both continuity and risk. On one hand, the model ensures stability and consistency—once appointed, a leader remains in office for life, avoiding frequent turnover or contested elections. On the other hand, historians and insiders raise valid concerns about the impact of advanced age on cognitive agility, organizational responsiveness and the ability to connect with younger generations.

Historian Gregory A. Prince notes that with longer life spans and improved health care among church leaders, the “gerontocracy” dynamic becomes more pronounced. He suggests that when leaders remain in full operational roles into very advanced age, questions about mental capacity or adaptability naturally arise.

The case for change

There is growing speculation—and historical precedent—that the LDS Church might consider embracing a different approach to succession. Options might include introducing mandatory retirement ages, designating emeritus status for senior appointees, or shortening terms of active service. Such ideas would mark a sharp departure from the church’s longstanding pattern and would require a bold leader willing to adopt structural reform.

Among the merits of reform:

- Infusing younger leadership could help the church connect more deeply with a changing global membership (now estimated at 17.5 million) and with newer societal patterns.

- A defined retirement or emeritus pathway could clarify roles and reduce uncertainty when a member is no longer able to serve at full capacity.

- Greater transparency might enhance institutional trust in an era when religious affiliation is increasingly fluid, particularly among younger adults.

The case for maintaining the status quo

Despite the arguments for change, there are strong reasons the church might hold to its current system:

- The “serve until death” tradition reinforces a sense of continuity and divine appointment in the eyes of many members.

- Sudden structural changes could raise theological, cultural or institutional complications—questions about authority, precedent, and the meaning of “prophet-president.”

- The church has managed growth and global expansion under the current system; its leadership may view change as unnecessary or risky.

What could trigger a reform?

Prince and other observers suggest that meaningful reform would likely require the impetus of a particularly bold and visionary leader. In other words: if Oaks (or a future president) were to launch reform, change would likely be deliberate, strategic and framed within a larger vision for what the church needs going forward.

Key triggers might include:

- A health or capacity issue in senior leadership becoming undeniable and prompting institutional action.

- A significant generational shift among members—especially in regions outside the U.S.—that demands younger leadership.

- External pressures: changing demographics, global expansion, or societal expectations about leadership transparency and succession planning.

Looking ahead

While the system remains intact today, the combination of aging leadership and global expansion creates a compelling moment of introspection for the LDS Church. Whether the institution opts to evolve its succession model—or recommits to the traditional lifelong service—will send a strong signal about its strategy and identity over the coming decades.

In short: The question is not just who leads the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; it’s how the future leaders will be selected, how long they will serve, and whether new structures will emerge to reflect a changing world.