Dumpster diving, the practice of scavenging through commercial or residential trash bins for usable items, operates in a legal gray area across the U.S., including Louisiana.

No statewide law explicitly bans it, thanks to a 1988 Supreme Court ruling in California v. Greenwood that discarded items lack privacy protections once on public property. However, trespassing onto private lots, local ordinances, and public safety rules often complicate matters for divers in the Bayou State.

Statewide Legal Framework

Louisiana follows the national precedent: trash abandoned in public spaces belongs to no one, making retrieval legal under general property abandonment principles.

Title 14 of the Louisiana Revised Statutes covers theft and criminal trespass (RS 14:63), but courts distinguish between owned goods and discarded waste—once curbside, ownership transfers to the public domain. State lawmakers have not enacted a blanket prohibition as of 2026, unlike some cities nationwide.

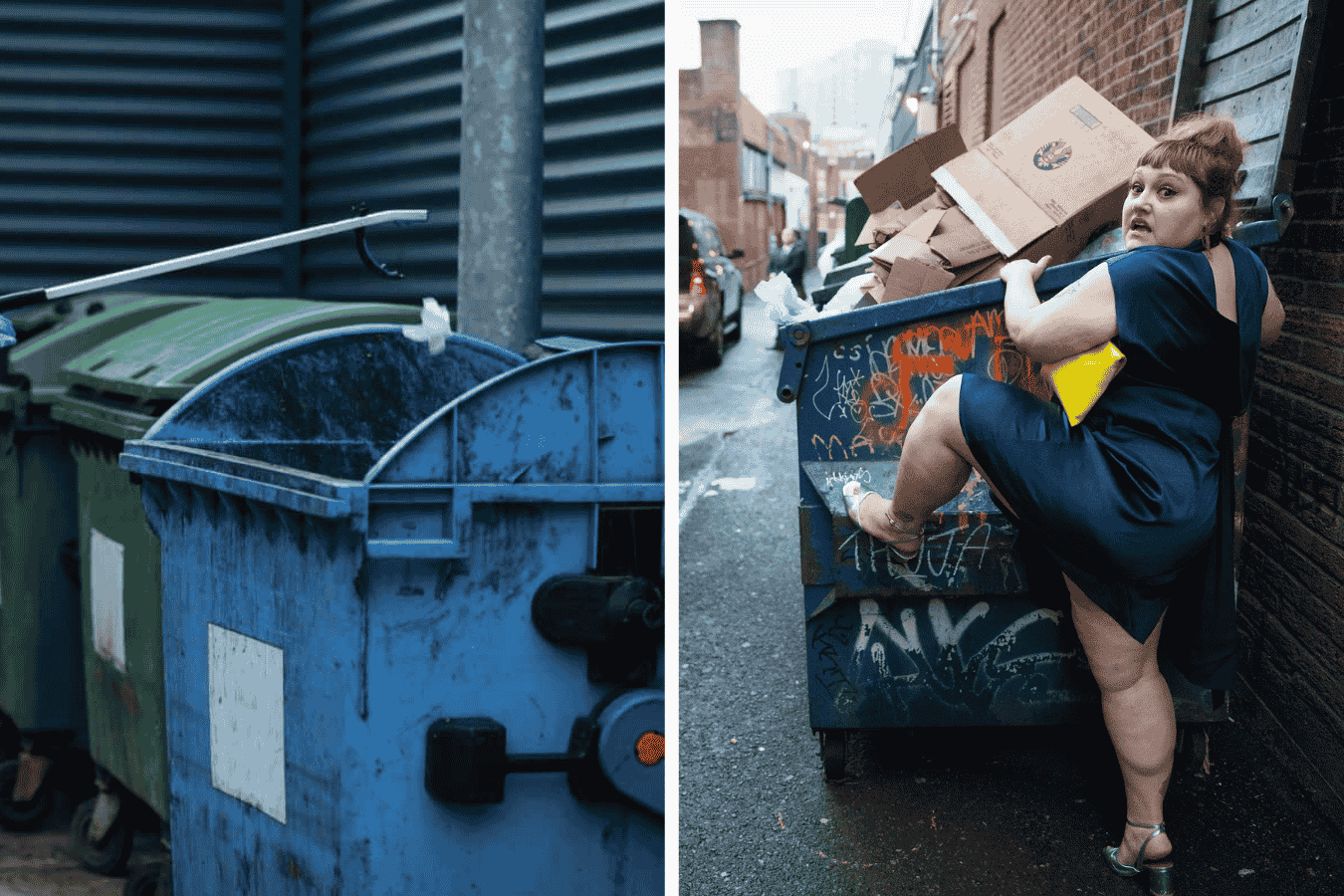

Key caveat: entering fenced, locked, or posted private property voids this protection, escalating to misdemeanor trespass with fines up to $500 and potential jail time. Public dumpsters along streets or alleys remain fair game if accessible without breaching barriers. Health codes under RS 40:4 prohibit handling hazardous waste, but everyday food or goods face no such bar absent contamination.

Local Ordinances and Variations

Municipalities dictate much of the enforcement. New Orleans, with its dense urban scavenging scene, tolerates diving behind restaurants and stores if divers avoid blocking alleys—though French Quarter bans post-10 p.m. loitering under nuisance ordinances. Baton Rouge enforces stricter no-trespass signs at commercial sites, with police issuing warnings before citations.

Rural parishes like Jackson lead crackdowns, passing anti-diving rules for community dumpsters to curb messes and protect recyclables intended for parish revenue. Shreveport and Lafayette mirror this, fining $100-$300 for “scavenging” public bins under littering statutes (RS 33:4169.1). Donaldsonville media reminds divers to check signage, as violations spike during Mardi Gras cleanup. Always scout city codes via municode.com or parish sites.

Private Property and Business Policies

Most U.S. dumpsters sit on private land, governed by “no trespassing” laws (RS 14:63). Chains like Walmart or Kroger post warnings; ignoring them risks arrest, as seen in 2025 Lake Charles cases where divers faced 15-day holds. Owners relinquish liability for injuries once trash is discarded, but messy aftermaths prompt disorderly conduct charges (RS 14:103).

Permission flips the script—many New Orleans grocers allow daytime dives, viewing it as waste reduction. Apps like TrashNothing.org connect divers ethically, sidestepping risks. Locked or gated bins signal clear no-go zones, per uniform trespass standards.

Health, Safety, and Ethical Concerns

Even legal dives carry hazards: needles, spoiled food, or tetanus from rusty edges prompted 2025 Louisiana Health Department alerts. Reselling finds skirts theft lines if not altered, but recyclables from municipal bins count as theft in some parishes. Divers should glove up, use headlights post-dusk, and clean sites to dodge littering fines ($200+).

Homeless advocates praise diving amid housing crises, but police prioritize vagrancy checks (RS 14:101) if encampments form nearby. Eco-groups promote it for reducing landfill waste—Louisiana discards 3 million tons yearly.

Enforcement Trends and Penalties

Citations outpace arrests: first offenses yield warnings or $50-150 fines for trespass or litter. Repeaters face misdemeanors (up to 6 months jail, $1,000 fine). 2025 data shows urban upticks tied to inflation, with New Orleans issuing 200+ tickets. Officers assess intent—quick grabs rarely escalate.

Defenses include proving public access or permission; body cams aid appeals in justice courts. Joining forums like SaintsReport.com shares real-time intel.

Best Practices for Safe, Legal Diving

Scout after closing hours when bins overflow legally. Target strip malls, apartments (curbside bags), and markets tossing produce. Flashlights, sturdy bags, and carts streamline; depart discreetly to avoid calls. Document permissions via notes or texts.

Alternatives: food banks, Freecycle, or Buy Nothing groups. In Louisiana’s humid climate, prioritize sealed goods. Network with local crews for hot spots—Baton Rouge’s Perkins Road proves fruitful.

SOURCES:

- https://www.rolloffdumpsterdirect.com/dumpster-diving-illegal

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/dumpster-diving-legal-states